1. Integrating Machine Learning with Physics:

My passion lies in exploring the intersection of physics and machine learning. I am intrigued by how machine learning can transform physics, enabling us to model, predict, and understand complex phenomena with unprecedented accuracy. I am eager to contribute to this evolving landscape by investigating and developing machine learning techniques that are tailored to physical applications.

Integrating machine learning with physics is a powerful way to blend data-driven insights with the foundational laws of nature. Consider, for example, the challenge of simulating unsteady fluid flow around a cylinder—a classic problem in fluid dynamics governed by the Navier–Stokes equations.

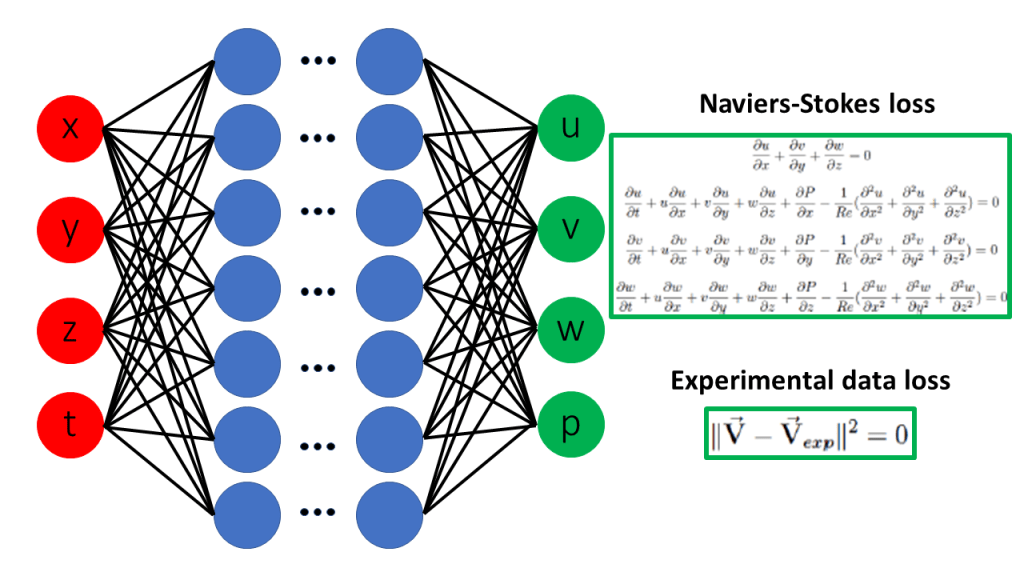

Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs)

PINNs integrate governing equations into neural network training by penalizing PDE residuals alongside data mismatch. A typical PINN loss function comprises:

- Data loss: discrepancy between network predictions and measured or boundary data.

- Physics loss: residual of the PDE (e.g., Navier–Stokes) evaluated at collocation points.

- Boundary/initial condition loss: mismatch at domain boundaries and initial time.

During training, automatic differentiation computes exact derivatives of the network output with respect to inputs, enabling direct enforcement of differential operators. PINNs thus require no mesh, only scattered collocation points through out the spatio-temporal domain.

Applying PINNs to Navier–Stokes

To solve Navier–Stokes with a PINN, one defines a neural network Φ(x,y,t;θ) that outputs velocity components and pressure. The loss aggregates:

- Residuals of momentum and continuity equations at collocation points.

- Enforcement of no-slip, inflow, or outflow boundary conditions.

- Optional sparse flow measurements for data assimilation.

Fig 1: Physics-informed neural networks for solving Navier–Stokes equations.

Advantages of PINNs for fluid flows

- Mesh-free approximation handles complex geometries without remeshing.

- Seamless integration of scattered sensor data for hybrid models.

- Potential for one-shot training on parametric families of flows.

2. Bridging the Gap: Solving Non-Linear Problems with Machine Learning

Non-linear problems are a hallmark of many complex systems in science, engineering, and finance. Unlike linear systems that follow straightforward proportional relationships, non-linear systems exhibit behaviors that can change dramatically with small variations in input. This inherent complexity makes them challenging to model using traditional analytical methods. However, machine learning, with its ability to learn patterns directly from data, offers a promising alternative.

One striking example is in the realm of physics, such as modeling turbulence in fluid dynamics. Turbulence is a deeply non-linear phenomenon where minute changes in fluid velocity can lead to unpredictable eddies and vortices. Traditional computational methods for simulating turbulence often require solving complex differential equations and can be prohibitively time-consuming. By contrast, machine learning models—especially neural networks—can be trained on simulation data to approximate these non-linear behaviors. Once trained, these models can quickly predict the flow dynamics under new conditions, providing faster and potentially more flexible solutions.

Another area where machine learning shines is in financial forecasting. Stock market data is notoriously non-linear due to its sensitivity to a plethora of unpredictable factors such as market sentiment, political events, and technological disruptions. Techniques like Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks are adept at capturing the temporal dependencies and non-linear relationships in financial time series data. As a result, these models can offer more accurate predictions of market trends compared to traditional linear regression models, empowering investors to make better-informed decisions.

In the field of signal processing, non-linear problems often emerge when trying to filter noise from complex signals. Traditional filters might struggle to capture the underlying non-linear relationships between the signal and the noise, leading to loss of vital information. Machine learning, however, can learn to distinguish the meaningful patterns from noise. For instance, by training on vast amounts of data, a neural network can be taught to recognize and extract the true signal even when the noise level is high.

At the core of these examples lies the remarkable capability of neural networks as universal function approximators. This means they have the potential to model any continuous function—even those riddled with non-linear complexities—given enough data and the right architecture. By leveraging this strength, researchers can develop solutions that not only predict outcomes with impressive accuracy but also provide insights into the underlying dynamics of the system.

In summary, my research interest in applying machine learning to non-linear problems is driven by the desire to harness data-driven methods to unlock new understandings where traditional techniques fall short. Whether it’s predicting turbulent flows, forecasting market behavior, or filtering noisy signals, machine learning offers a versatile and powerful toolkit. This interdisciplinary pursuit not only pushes the boundaries of technology but also contributes to a deeper, more nuanced understanding of the complex, non-linear systems around us.